Early in my project management career, I had the opportunity to work with a talented developer. I’ll call him Sam. Sam was smart, for sure, and he knew it. He also knew he was the only person who deeply understood some critical modules of the software we were developing.

However, Sam struggled with emotional intelligence, and he was often oblivious to how his words and negative actions impacted others. If someone disagreed with him, he tended to write them off as stupid, and he could easily lose his temper in meetings. He refused to follow many of our internal processes because they were, in his opinion, worthless. In short, team members and business stakeholders trod lightly around Sam, hoping they wouldn’t set him off.

Past bosses put up with Sam’s belligerence because he was technically valuable—we couldn’t afford to upset him or risk losing him to a competitor. The company was dealing with a ticking time bomb. After being passed from group to group, Sam landed in my organization. I was the last remaining manager for Sam to work with, and I was a relatively inexperienced manager at that.

What was I to do with Sam?

What We Tolerate

A couple of years ago, in a book about respecting people’s boundaries, I came across a quote: “You get what you tolerate.” [1] It was used in the context of marriage relationships, but it applies to many areas of what we do as professionals. This is especially true for those of us who lead teams that deliver software projects.

Everyone, especially management, tolerated Sam. But the impact of his behavior was more disastrous to team members. Trust quickly eroded when the tsunami of Sam’s wrath crashed against someone in his way. Beyond hurt feelings, it hindered productivity and led to increased attrition.

This problem is not unique to software development teams. Sales-oriented organizations often tolerate destructive salesmen as long as they make their numbers, and some organizations tolerate hopelessly demanding and abusive customers because of one reason: “We need the money.”

So, what are you tolerating? In my work with software managers around the globe, I often see three areas where we get what we tolerate:

- Team member performance

- Conflict among team members

- Our own careers

Individual Performance

It’s easy to start tolerating lackluster performance. Engaged, self-managed teams are a worthy aspiration, but over time, certain team members consistently go above and beyond while others barely carry their own weight.

The incorrect perception is that the lower performers on your team may be lazy. It could be they have just gotten into a rut and need to be challenged. It could be the low performers are sufficiently competent but realized how compensation works at many organizations—they can go above and beyond and get a 3 percent raise, and the person who scarcely has a pulse gets a 2 percent raise.

Regardless, an objective analysis of your team would likely find that you are tolerating lower performance from some team members.

How much does this matter? Researchers of team effectiveness examined the impact of team members who were deadbeats (defined as “withholders of effort”), downers (who tend to “express pessimism, anxiety, insecurity, and irritation”), and jerks (who violate “interpersonal norms of respect”). They concluded that tolerating only one of these negative people can bring down overall team performance by 30percent to 40 percent. [2]

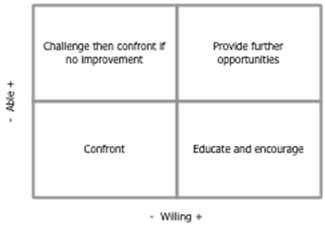

The willing/able matrix shown in figure 1can be used to help guide team members to maximum effectiveness.

Figure 1: How to move from tolerating to improving

Figure 1: How to move from tolerating to improving

The goal is for team members to operate in the upper-right quadrant as fully able (competent and skilled) and willing (engaged, motivated, and open to change).

Sam was fully able, in that he was clearly a talented developer. But he had a willing problem. This placed him in the upper-left quadrant of the matrix. Folks in that quadrant need to be challenged to move to the right. This can lead to the manager confronting individuals if their performance doesn’t improve.

Conflict and Team Interactions

Beyond individual performance issues, we can also tolerate poorly managed conflict between team members. Teams inevitably encounter conflict, and if you’re a manager at all like me, you may not particularly look forward to dealing with it. Yet how your team deals with conflict can be a critical factor in how successfully you deliver your projects. It can be a good thing and lead you to better solutions, or it can be destructive, leading to reduced trust, resentment, and attrition.

Cognitive conflict is the beneficial sort of conflict—the type that wrestles with the ideas and approaches that lead to better outcomes. Cognitive conflict is also necessary, and if you don’t have some of it, you could be tolerating something just as insidious: artificial harmony. Affective conflict, on the other hand, is when those interactions go over the line and get personal. Tolerate affective conflict, and it’s only a matter of time before you’ll see hits to innovation, quality, and overall team performance.

Talk with your team about these types of conflict and be alert to situations where you begin tolerating affective conflict.

Impact to Career Progression

How about you? What are you tolerating in your career? Have you grown strangely content working for an organization that treats you more like a resource than a person? Are you tolerating a boss who micromanages you and shoots down ideas without reasonable consideration? Are you settling for a paycheck, having given up on pursuing a path that would be more meaningful but risky?

In his book Workplace Poker, [3] author Dan Rust suggests that if you’re not happy with the state of your project, the performance of your team, or where you are in your career, there’s only one person to blame: yourself. Rust’s point is that until you take responsibility for where you are, you won’t take responsibility for improving your situation.

The best help I’ve found for handling career tolerations is a mentor. It’s often too difficult to get the perspective we need on our own. Regardless of how formal the relationship is, substantial benefits come from having someone who can help assess where you are, where you would like to go, and how to get there.

Your Next Move

The willing/able matrix helped me start a long overdue conversation with Sam. I challenged him to find an opportunity to grow his influence at the organization and to improve the team’s overall ability to deliver. When Sam pushed back and refused to change, this eventually led to a more difficult conversation. Sam was now confronted with the reality that if he didn’t change, it would cost him his job.

I wish I could report that Sam’s eyes were opened and he changed his behavior. In the years since, I have seen problem employees respond favorably to challenges and up their game. But that’s not how things ended for Sam. I took the step we had all avoided for too long, and Sam was asked to leave the company. This resulted in Sam without a job and our team missing this highly volatile but valued developer.

That seems like a lose-lose ending, but it’s not the end of the story.

How long do you think we missed Sam, whom we thought we couldn’t live without? Not long. Team morale and productivity improved, and we were still able to complete projects. It turned out to be a positive experience for Sam, too. His wife happened to attend a class I was teaching years later. During a break, she told me that being let go was a terribly difficult time for him, but he could now say it was one of the best things that happened in his career. It was the jolt he needed to make some necessary changes in his life.

You are getting what you tolerate, with your team and your career. Some of these results are benign and unworthy of further thought. But others are holding you and your team back from maximizing true potential. It’s your responsibility to remove anything impeding your team.

What are you tolerating?

References

- Cloud, Henry, and John Townsend. Boundaries in Marriage. Grand Rapids, MIC: Zondervan Publishing House, 2002.

- Sutton, Robert. “How a Few Bad Apples Ruin Everything.” Wall Street Journal. October 24, 2011. wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052970203499704576622550325233260.

- Rust, Dan. Workplace Poker: Are You Playing the Game, or Just Getting Played? New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2016.