In 2007, The Pixar Story, a new documentary, was screened at the Mill Valley Film Festival. It chronicled the studio’s founders’ crazy activities as they worked to create a new sort of film—a totally computer-animated film overflowing with exuberant colors and textures, ultra-vivid characters, and plotlines subtly laced with mind-expanding wisdom. The interviewer then offered a daring question during a panel discussion that followed“ is there any connection between the world of the counterculture and psychedelics, and Pixar?”The panelists on stage, Ed Catmull and John Lasseter, both pivotal figures in Pixar’s growth, became silent. For the staff of a Disney division revered by generations of youngsters, drugs and the counterculture are taboo topics.

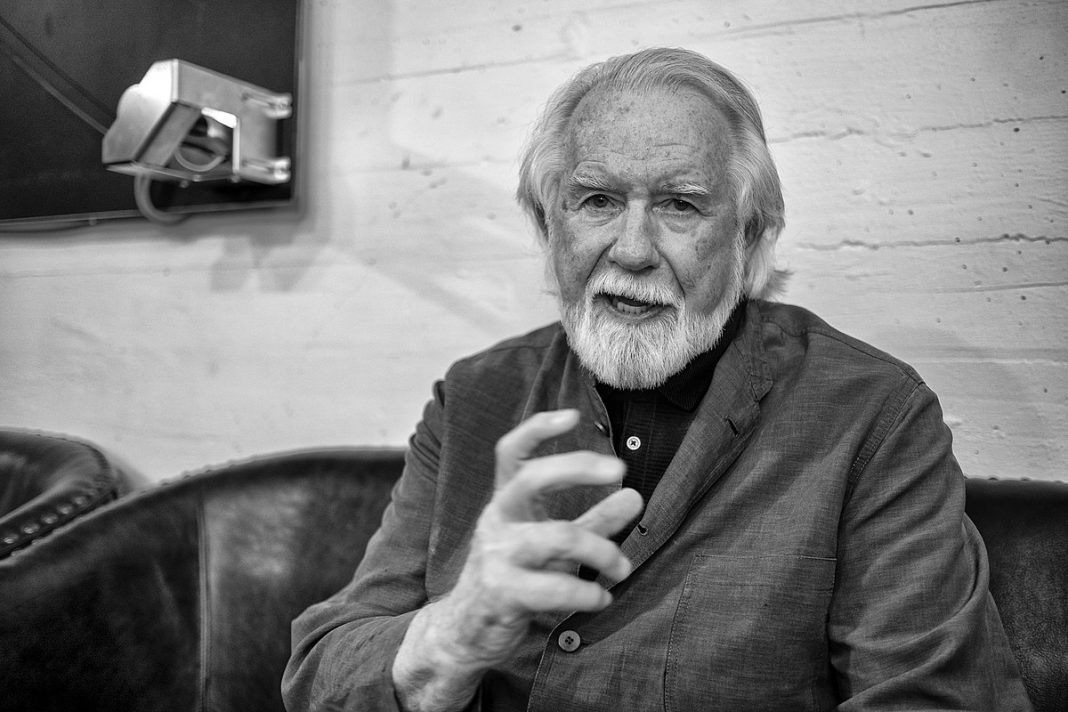

If Smith, the bearded, exuberant co-founder of Pixar, had been given the opportunity to respond, he would have readily conceded that LSD influenced his creative orientation, which in turn influenced Pixar’s culture and technology. Smith departed the company just as it began making actual pictures, yet he is responsible for every frame of those films. He was instrumental in the development of breakthroughs that allowed movies to be created purely by code and algorithms. He also made significant contributions to the earliest digital paint program, coding up elements that altered our ability to manipulate images, both before and after Pixar. But Smith’s presence in the back of the auditorium—and not on the stage—spoke to something else: the dissonance between his contributions and his fame.

Smith, like a computer graphic muse, helped Pixar get closer to the promised land. He did not, however, enter it personally. From Bug’s life to my ratatouille to my spirit, I’ve seen it all. The studio pushed the boundaries of technology and creativity, fulfilling Smith’s vision while on the full-body cast, acid cruises, Long Island mansions, and much of Lucasfilm’s backyard. His former Pixar coworkers are unequivocal in their praise for his achievements. Smith’s name was taken off the site after he left, which he believed was a betrayal. Catmull claims that the web pages are not historical documents. However, the 77-year-impact old’s isn’t limited to the past, and the rest of the world is still catching up to him. He eventually took the plunge last summer, releasing A Biography of the Pixel, a book in which he lays out a grand unified philosophy of digital expression. Pixel is a dense and difficult book in the vein of Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, a weaving saga of science, heroes, and dictators that culminates in a long-foreseen digital convergence sometime around the turn of the century. Almost all forms of expression—visual, textual, audio, video, you name it—have shifted to the machine world, which, contrary to popular belief, is just as real as our physical reality. That isn’t a metaphorical equivalency, either. Smith claims that it is literal.

Oh, and the pixel, the topic of this biography, isn’t what we believe it is. Forget about your erroneous idea that a pixel is one of your screen’s tiny squares. According to Smith, a pixel is the result of a two-step process in which an element of purposefully created material is displayed on a display. Friends, you are looking at the expression of those pixels on your screen, not the pixels themselves. Digital Light is what you see. What about the pixel itself? That’s only a thought. It’s evident that Digital Light isn’t a second-class reality if you understand the distinction. It is equal in the twenty-first century.“Just the simple idea of separating pixels from display elements is going to seem revolutionary to people who don’t understand the technology,” Robertson says.

Smith was an excellent student who excelled in arithmetic. He enjoyed spending time with an uncle who was a professional artist, however. Uncle George let only Smith into his studio, and the kid quietly studied how to stretch a canvas, mix oils and turpentine, and utilize pigments to bring a blank canvas to life. While visiting scientists at the adjacent White Sands Missile Range, he received a taste of computer programming. He studied electrical engineering at New Mexico State University before going to Stanford to study artificial intelligence. He learned more than computers in California.

The last months have had a significant impact on startups, according to statistics. Photoshop introduced a competitor feature named “Layer” at the time. Altamira’s sales are at an all-time low, and the company is in desperate need of a lifeline. Nathan Myhrvold, the head of Microsoft Research, was introduced to Smith.“I just want to get marketing help from Microsoft,” Smith said. Instead, Myhrvold bought the company, even though he wanted Smith more than his products. Smith stayed there for four years and retired in 1999. “Along the way, I decided that they didn’t really care about my thoughts,” Smith’s next career choice shocked his peers: he became a genealogist. He began meticulously researching his ancestors and was named a Fellow of the American Society of Genealogists in 2010. The award is only given to 50 people who are still living, and it requires an absolute majority of votes to be granted.