Domestic tasks appear to have joined the fray with the emergence of AI and Machine Learning and their use for various industrial and economic goals.

As a result, the demand for additional technological advancement has reached its peak.

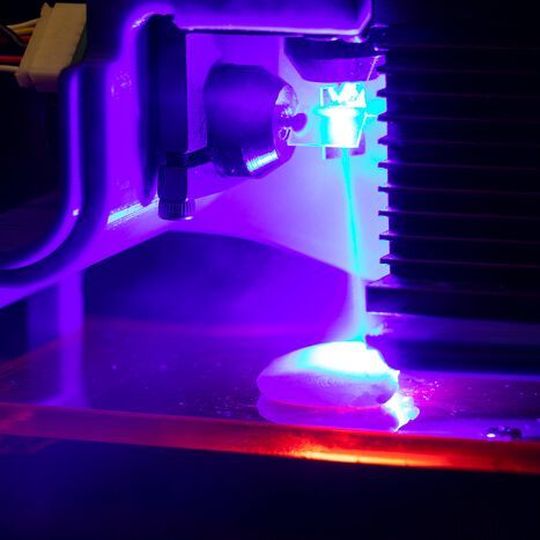

Imagine having your own robotic chef at your disposal, ready to make whatever you want, exactly to your liking, at the touch of a button. Columbia Engineers have opted to make things easier with the invention of software-controlled robotic lasers that not only cook food with exceptional precision but also provide a completely new, customized approach to cooking a delectable meal, according to a new study published in npj Science of Food. The engineers proposed using lasers for cooking and 3D printing technologies for food assembly.

The team has recently concentrated on constructing a fully autonomous digital personal chef under the guidance of Hod Lipson, a Professor of Mechanical Engineering, and his “Digital Food” team of Creative Machines Lab. Since 2017, the group has been producing 3D-printed foods, and food printing has advanced to multi-ingredient prints, which are currently being investigated by researchers and a few commercial enterprises.

“We noted that, while printers can produce ingredients to a millimeter-precision, there is no heating method with this same degree of resolution,” said Jonathan Blutinger, a Ph.D. in Lipson’s lab who led the project. “Cooking is essential for nutrition, flavor, and texture development in many foods, and we wondered if we could develop a method with lasers to precisely control these attributes.”

The Lipson team experimented with various cooking methods, utilizing chicken as a model food system and exposing it to blue light (445 nm) and infrared light (980 nm and 10.6 m). 3 mm thick chicken samples with a 1in2 area were printed.

as a testbed, the researchers looked at a variety of factors such as cooking depth, color development, moisture retention, and flavor differences between laser-cooked and stove-cooked meat. It was determined that laser-cooked meat shrinks 50% less than conventionally cooked meat, retains twice the moisture content, and develops flavors similarly.

With both Lipson and Blutinger showing their excitement on the prospect of this new technology that has fairly low-tech hardware and software components, they jointly opined that a sustainable ecosystem is not yet available to support the technology. Lipson himself noted that “what we still don’t have is what we call ‘Food CAD,’ sort of the Photoshop of food. We need high-level software that enables people who are not programmers or software developers to design the foods they want. And then we need a place where people can share digital recipes like we share music.”