Digital infrastructure is almost as essential as power, water, and transport. For this reason, data centers have become the darling asset class for investors over the past decade.

InQ4 2021, APAC overtook the Americas and EMEA for the first time in terms of new data center commitments. The wave of investment is not slowing down, and hundreds of millions of people are digitizing at a rate never seen before.

This month alone, Blackstone announced a $25bn commitment to a brand new India-based data center platform, “Lumina CloudInfra”. A few weeks earlier, KKR, who already owns CyrusOne and several cell tower businesses, raised a record-breaking $6bn Asia Infrastructure fund in addition to their existing $2.7bn Real Estate fund for the region.

But as we head into 2023 and clouds of economic gloom circle the world economy, particularly big tech, do the more significant risks of emerging markets outweigh the potential rewards?

In other words – is there still gold in them hills?

What makes Asia difficult?

Asia has always been viewed as a tough nut to crack.

Equinix is the biggest digital infrastructure company in the world. The market leader by most metrics entered APAC in 2002 through a deal with Singapore’s ST Telemedia. Twenty years later, the titan of digital infrastructure still only makes around 20% of its sales(according to this quarter’s earnings call)from a region with 60% of the world’s population.

Foreign investors have many reasons to be cautious, such as the myriad of languages, currencies, and cultures. Among many reasons, here are three factors specific to digital infrastructure which can sometimes make Asia a daunting prospect for would-be investors:

- Regulation

They are permitting, planning, land acquisition and ownership. While Singapore and Australia might have standard rules, significant markets such as Japan, Korea, and China have entirely alien systems requiring local partners to navigate. Meanwhile, India, Indonesia and the Philippines are each a different ball game. As with all developing markets, risks associated with corruption are present, particularly in real estate and construction. With data centers, these old-fashioned risks meet modern technology’s complexity (and legal vagueries), rendering contracts vulnerable and settlements far from guaranteed.

- Manpower

This is ubiquitous across tech sectors, but two factors add to the acute shortage of skills here. Firstly, while the language of big tech is English, industries like real estate, construction and nationalized telecom companies often deal in their local language, which means that there is a bilingual requirement compounding the technical skills shortage. Secondly, the shortage of data centers (see below) means a lack of people with experience building them.

- Supply Chain

Data centers are high-tech buildings filled with equipment that is designed, built and crucially repaired in developed markets. A US cloud tenant demands familiar components from known brands and 24/7 uptime; however, the nearest service center is an overnight flight and 12 time zones away. This adds a layer of logistics and cost, which at tight margins could be prohibitive. This is, of course, assuming equipment is available with current hardware constraints and currency fluctuations.

How big is the opportunity?

It would be easy to assume that advanced cities like Shanghai, Tokyo and Singapore are already well-supplied with digital infrastructure. After all, their trains, airports and hotels can feel decades newer than their counterparts in New York and London.

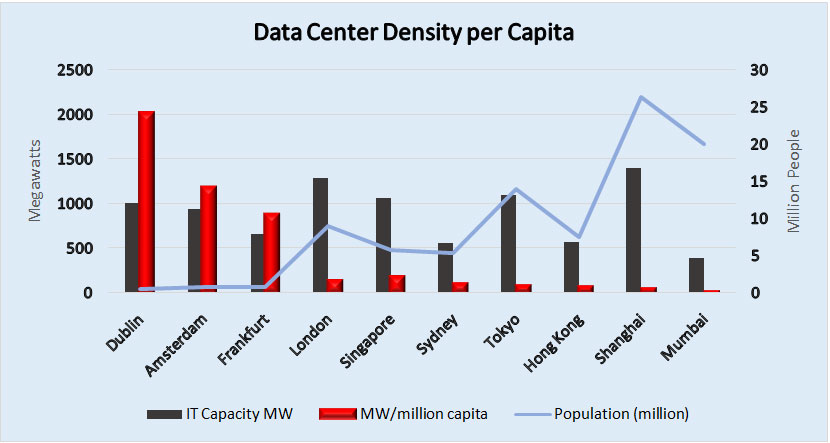

“IT Capacity” of data centers in the city either live or currently under construction (not including planned/in development)from the 2021 Q4 report by Knight Frank and DC Byte. The top graph takes the top 10 cities in EMEA and APAC from this report and compares the volume of data centers against population.

“IT Capacity” of data centers in the city either live or currently under construction (not including planned/in development)from the 2021 Q4 report by Knight Frank and DC Byte. The top graph takes the top 10 cities in EMEA and APAC from this report and compares the volume of data centers against population.

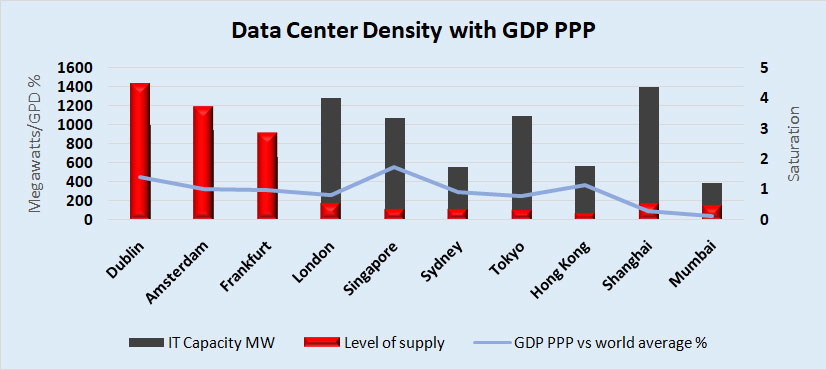

GDP per capita with Purchasing Power Parity (per IMF data) for the country is expressed as a % against the world average.

GDP per capita with Purchasing Power Parity (per IMF data) for the country is expressed as a % against the world average.

The second graph combines GDP PPP and Population against MW IT Capacity to indicate how well served or how saturated each market is.

By comparison, Dublin is up to twelve times better serviced than Singapore “pound for pound”, while Amsterdam is ten times more saturated than Tokyo. Even in raw numbers, Frankfurt (Germany’s 5th city) has more data center capacity than Hong Kong and Mumbai combined.

This is not to suggest Dublin, Amsterdam or Frankfurt are bad investment markets.All of the top European cities have 100% more capacity in development – that is to say, when the current pipeline of data centers is built, all of these cities will double in capacity.

Instead, this shows the scale of the opportunity in Asia.

These numbers are crude, and because of a general lack of transparency in the industry, it is impossible to account for things like the number of surrounding towns or cities these data centers support as hubs. However, we can see clearly that Asia is critically underserved with regard to cloud infrastructure.

The Road Ahead

The same demand macro factors as in the rest of the world, namely digitization. The growth of the cloud and the explosive growth of video and photo data are present in Asia, and that’s not to mention less substantive future drivers like AI, 5G or self-driving cars. These macro trends combine with the chronic supply shortage we see above.

2023 might be a tough time to raise and access capital, with many twists in the road, but for those who can commit time and resources, the opportunity is there to be seized.

###

Rhys Morgan is an Associate Director and Head of Digital Infrastructure at Singapore-based Executive Search firm, Kepler Search. With over ten years in recruitment, Rhys accumulated his leadership hiring experience in Europe and the USA and has been doing Asia leadership recruitment in Singapore for the past four years. Rhys works with local and international investors who build Data Centers, Cell Towers,/Optical Fibre (Digital Infrastructure).