The part of a store run that stays with us the longest is the horrible experience of seeing regular folks like us turn on each other abandon our sense of altruism even as we clamor to shove items into our respective carts. It’s even worse when we exhibit such behavior for essentials like food and medicine. Scenes of frenzied buying of toilet paper, hand sanitizers, masks, bottled water, and lifesaving drugs during the early days of the pandemic are going to stay in our collective memory for a long time; perhaps forever.

These images, to me, are emblematic of all that has gone wrong with the supply chains in the last four decades. So bad that even after more than two years of the Coronavirus showing up on our shores, our supply chains have stayed hit. Container ships unloading goods stayed longer at American ports in the last three months than they did even at the pandemic’s start. Our most prominent companies, including Apple, GE, and Mondelez, have warned that their supply chains will stay constrained for the foreseeable future. More than a third of America’s C-executives responding to a recent PwC survey foresaw continued supply chain disruptions. News and images of food shortages continue to emerge worldwide, including the U.S. The problem of semiconductor shortage persists.

Two years is a long time for any intelligent system to learn from its errors and correct its course. That does not seem to have been the case with our supply chains.

Naturally, questions abound. What’s wrong with our supply chains? How did the pandemic catch our supply chain managers napping? And as significantly, what can be shored up to address the situation?

These are some big existential questions about a mammoth system as old as the civilization itself. There can be no simple answers. But considering the crisis that we are facing, questions must be asked and solutions sought. Many observers have, for example, asked whether a big problem with our supply chains is that they are too lean? “We went way too far,” a recent NYT article quoted a McKinsey partner about the lean mentality adopted by industry strategists. A 2021 WSJ article entitled “Why are there still not enough paper towels?” squarely (pun unintended) blamed the shortage of essentials on lean manufacturing.

It appears that a good number of industry professionals also share the sentiment. CSCMP’s 2021 Third-Party Logistics Study found that 42 percent of respondents felt, based on their pandemic experience, that supply chains were “too lean.”

There is no doubt that the charge of supply chains, having gone far too lean, has some weight. However, making them lesser lean – our warehouses better stocked – is an easy answer. After all, by definition, a catastrophe defies our best estimation and preparations. With that stated, we must evaluate this claim in this article.

Also, we must keep in mind that no amount of resilience can ward off panic buying that triggers a low loop and a resultant supply outage. A more significant cause for concern is the sustained disruption of supply chains when the initial blow has kept the supply chain struggling on its feet.

Clearly, besides the ‘too lean’ issue, there are other issues at play. The elephant in the room, in my view, is the single-strand supply chain that serves us in the U.S., with demand centers concentrated at one end and supply centers at another. To understand the severity of this issue, let’s take a quick look at the problem of chip shortage and the way it has impacted the automotive industry.

Chip shortage: A symptom of a deeper problem

In February last year, a global chip shortage brought car production in three states to a halt. Governors of Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, Kansas, South Carolina, Alabama, and Missouri wrote to President Biden to urge global semiconductor and wafer companies to expand production and “temporarily reallocate a modest portion of their current production to auto-grade wafer production,” reported Reuters.

The world was then in the grips of a chip famine, which has since abated, but not before having created a situation that cost the automotive sector globally an estimated $210 billion in lost revenue in 2021, according to consultants Alix Partners.

The shortage of semiconductors can be traced to the peak of the first pandemic wave in July 2020, when spooked by lockdown restrictions, carmakers in the U.S. and elsewhere scaled back their procurement of semiconductors. This prompted the chip manufacturers – the vast majority of whom are based outside the U.S. – to re-direct their production lines to the electronics industry facing a demand surge due to the pandemic-induced trend of remote working.

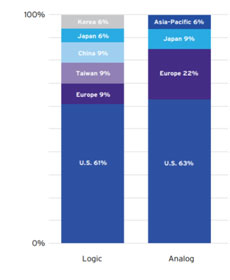

From a larger perspective, it hasn’t helped that America’s share of global semiconductor fabrication has reduced from 37 percent in 1990 to a meager 12 percent today. Notably, more than 75 percent of semiconductor fabrication is now localized in Asia. As notably, China’s share of chip manufacturing trajectory presents a sharp contrast, going from zero to close to30 percent in the same period. Demand-wise, however, the U.S. remains unbeatable (Figure 1).

The problem of the shortage of semiconductors is an important example in how it shows us that even the most sophisticated best practices, demand forecasting tools and the advanced data analytics practiced in two of the most technologically advanced industries – automotive and electronics – cannot help if supply chains suffer with structural deficiencies.

How we got here

How we got here

Blame it on a supply chain made for the good times, of the good times. Or, in other words, a global supply chain that began shaping up during the shopped-till-we-dropped decade, to use an LA Times moniker.

From all accounts, the meeting of two distinct trends during this era began to create the structure of the global supply-chain strand that serves America today. These two trends were: a booming consumer demand at home and the other was lowering trade barriers which ushered in globalization.

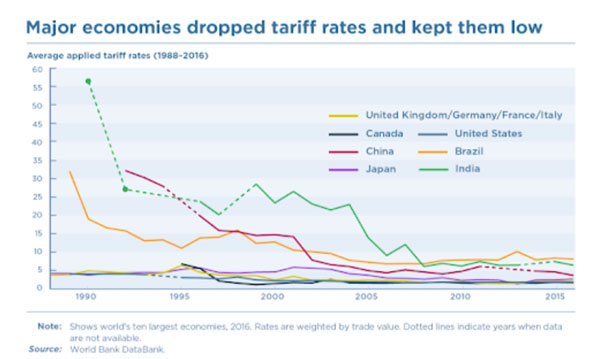

Reagan and Thatcher – the champions of the free-market economy – echoed the voice of a brave new world that wanted to trade. This was the first time in America’s economic history that the average family spent more on purchasing a car than it did on total food at home. The wages also saw growth, but inflation had to be kept under check. The fall of the iron curtain in 1989-90 and the end of the cold war of 1991 heralded an era when the biggest economies embraced the idea of a truly global economy. In 1989, exports rose to 14 percent of global GDP – its highest level since the pre-world-war years. The following few years saw significant economies drop trade tariffs to unprecedented lows, where they have stayed since (figure 2).

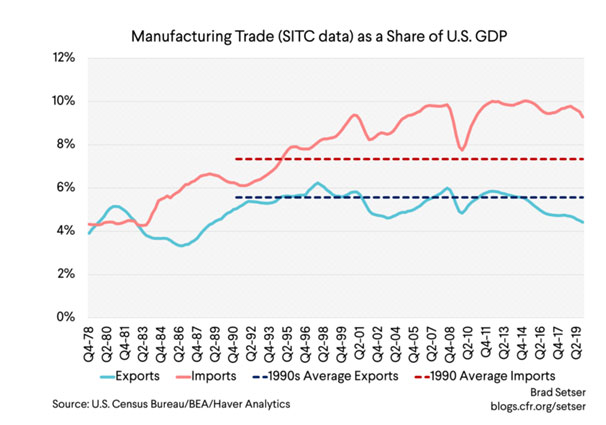

The lowering of trade barriers gave producers the world over a great opportunity to fulfill the demand of consumers in high-income countries, including the U.S. As a result, imports to the U.S. rose substantially since the 1980s; however, the share of exports stayed at the same level and even began to fall by the 2010s (figure 4).

The meeting of these two trends – rising consumption and globalization – worked well for the American consumer. Manufacturers, however, were hit by the rude realization that globalization is a two-way street. They met their worthy contenders when Japan, the one only Asian country that figured among the world’s top five manufacturers up until the 1970s, leapfrogged every other country in the eighties to go head-to-head with the U.S. This was a time when each produced close to one-fifth of the world factory output.

As our older readers will recall, Japan’s roaring success made quite a few headlines back in the day. Researchers, columnists, and consultants rushed to Japan to learn their secret sauce, the reason the former foe was able to leverage globalization and indulge in a “one-sided trading,” as a The Atlantic article noted.

Reasons proffered ranged from Japan’s protectionist policies that sought to keep its home consumption low and corporate profits high to charges of undercutting competition from local and foreign sellers in the United States.

Enter, Lean

During the mid-to-late-seventies, some scholars and industry associations were documenting a little-noticed practice that they felt was responsible for the spectacular performance of Japan’s automotive companies, led by Toyota. An academic paper entitled Toyota production system and Kanban system Materialization of just-in-time and respect-for-humansystem, considered the earliest source on Toyota’s JIT system, was the first to appear on the subject in English in 1977. Another important work, during the same year, appeared in the magazine American Machinist. Anderson Ashburn, the magazine’s editor, wrote about this unique management system in a 1977 article titled “Toyota’s ‘Famous Ohno System.'” He had written the piece following a visit to Honda’s motorcycle plant in Japan, where he noticed that there was almost no work-in-progress inventory.

However, it took several years before American companies recognized the brilliance of this unique system. By the mid-eighties, it had become relatively well known among the manufacturers. Mentions of JIT/TPS (Toyota Production System) were in many case studies published around the mid-eighties. A particular 1986 case-study book devoted a chapter to a system called ZIPS (Zero Inventory Production system) that Omark Industries (later Oregon Tool), an equipment manufacturer, has formed based on JIT. The book had two other chapters on JIT at several HP plants, Harley-Davidson, John Deere, IBM-Raleigh, North Carolina, and Apple Macintosh[1]. Subsequent research and scholarly work, notably John Krafcik’s 1988 article “Triumph of the Lean Production System” and MIT’s seminal 1991 credited with internationalizing lean production, The Machine That Changed the World, made lean production or lean thinking integral to manufacturing. This was also a time when supply chain and logistics as distinct disciplines were taking shape in academia and the industry. The SCM concept, for example, was coined in the early 1980s by consultants Oliver and Webber[2]. They posited that supply chains must be viewed as a single entity, and strategic decision-making at the top level of the chain was needed to manage it effectively (Kransdorff, 1982). The lean philosophy and its principles were extended to supply chain and logistics operations in the following years. Today, lean is regarded as among the most influential movement to have shaped the way things are manufactured and distributed, and rightly so. During the last thirty years, globalization has changed the nature of competition between one between businesses to that of being one between supply chains.

The afforested genealogy of lean – focusing on the events that led to its adoption in the U.S. and subsequently the world – provides an informed view into one of the questions posed at the beginning of this article: should the present, fragile state of supply chains be blamed on lean? Here’s where I stand: the problem lies not with lean philosophy but how it was adopted here in supply chains in the United States and the world.

In America, lean was adopted – or re-adopted if you take Ford’s flow production system being the origin of the lean idea into account – to cater to a booming economy. However, in Japan, it was developed in response as an antidote to disruption; therein lies the critical difference. A closer study of Toyota’s formative years will reveal a troubled start. Within a few years of inception, the automaker found itself grappling with wartime curtailment of the use of raw material during the Second World War. This was soon followed by an air raid that nearly destroyed its facilities, which faced a mass resignation of employees no longer bound by wartime conscription rules. Again, within a few years of resuming production, the automaker was hit by labor strikes bringing it to the brink of bankruptcy, forcing the founder Kichiro Toyoda out in 1950. During the same year, Eiji Toyoda, the founder’s cousin and managing director, visited Ford Motor’s River Rouge plant and came back taken in by Ford’s scale, though unimpressed by its inefficiencies. His experience there led him to team up with a veteran loom machinist, Taiichi Ohno, to fine-tune their company’s operations. The duo then developed concepts like Kanban and Kaizen that formed the core principles of The Toyota Way. In simpler words, Toyota’s lean system was a philosophy forged by fire.

Therefore, it emerges that the global supply chain network was built for the cheaper cost to serve high yield markets as it began shaping up in the eighties. The corporate strategists adopted lean practices for competitiveness but not for resilience; herein lies the design flaw that the pandemic has laid bare. As examples of how Toyota’s (and those of other Japanese automakers’) supply chains are built for resilience, consider two often-overlooked factors: Keiretsu, Japan’s traditional supply system, and the geographical spread of its suppliers.

The hierarchal structure of a Keiretsu incentivizes suppliers to work together for the common good and ensure their survival (Cusumano and Takeishi 1991, Clark and Fujimoto 1991).

Building such a network requires companies to nurture relationships that survive and step up during disruption. As an HBR article noted, once a darling of business schools and manufacturers everywhere, Keiretsu fell off the radar as cost became the more significant concern in the U.S. Japanese automakers, however, revived the practice in recent decades. The new, reinvented Keiretsu is about forming supplier relationships that are not only richer and deeper but are also more global and cost-conscious. This is one lesson for our strategists to keep in view at the time of designing our supply chain networks.

The practice of Keiretsu also entails that companies locate their suppliers as geographically close as much as possible. This has helped Japanese automakers through the various disruptions. As an NYT article pointed out, Toyota has been among the automakers least affected by the semiconductor shortage because the company, from the days of inception of JIT, relied on suppliers located close to its base in Japan, “making the company less susceptible to events far away.” Sure enough, a comparison of the geographical spread of General Motors with that of Toyota provides a study in contrast. Plain near-shoring of suppliers is presently more of a reactionary and counter-productive approach – one more instance of the proverbial all-eggs-in-one-basket solution – and not a long-term, balanced approach to finding a solution. A better way would be an approach that I’ve long been advocating, which I call the decoupling of supply chain networks.

A decoupling point is a concept in inventory management where a specific inventory-holding point is established close to the operational zone. The decoupling point acts as a strategic distribution hub and a safety buffer that protects that regional supply chain network from demand shocks. Here’s what I mean by decoupling of the supply chain: instead of having a single-strand global supply chain, which is susceptible to a shock anywhere along its length, a more resilient form would comprise a network of regional supplier clusters, each situated close to demand centers, each network connected to the other through decoupling points. I expect supply chains of the future to be formed along these lines, as it will help make our supply chains both competitive and resilient.

The pandemic has ensured that the next phase of evolution in adopting lean in healthcare and other services will be to build an enterprise system that provides a customer-centric solution. Even the original lean transformation process was not about working with reduced inventory. It was meant to drive enterprise excellence and not at the expense of agility and resilience. Our single-strand supply chain, where we became overly dependent on one or more supply chain clusters, was not shaped by lean—the very practice of lean preaches building redundancy, agility, and resiliency.

Experts in academia and industry have always long implored supply chain organizations to integrate risk management practices like FMEA (Failure Mode and Effects Analysis) and PPRR (Prevention, Preparedness, Response, Recovery) into their strategy and operations. The present crisis has exposed the structural flaw of our supply chains that are built more for cost and speed and less for resilience.

[1] Stark, A. (2019). Supply Chain Management. United Kingdom: EDTECH.

[2] Pounder, Paul. (2013). A Review of Supply Chain Management and Its Main External Influential Factors. Supply Chain Forum. 14. 42-50. 10.13140/2.1.3787.3289.

……………………………………………………………………………………………..

Dr. Nick Vyas | LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/thevyasusc

Dr. Nick Vyas is an educator, global thought leader, author, keynote speaker, American Society for Quality (ASQ) Fellow, Chair of the ASQ Lean Division, and legal advisor to leaders in the worlds of supply chain and global trade practice and policy. As the founding Executive Director of USC Marshall’s Kendrick Global Supply Chain Institute and Academic Director of the M.S. Global Supply Chain program, Dr. Vyas educates the next generation of business leaders.